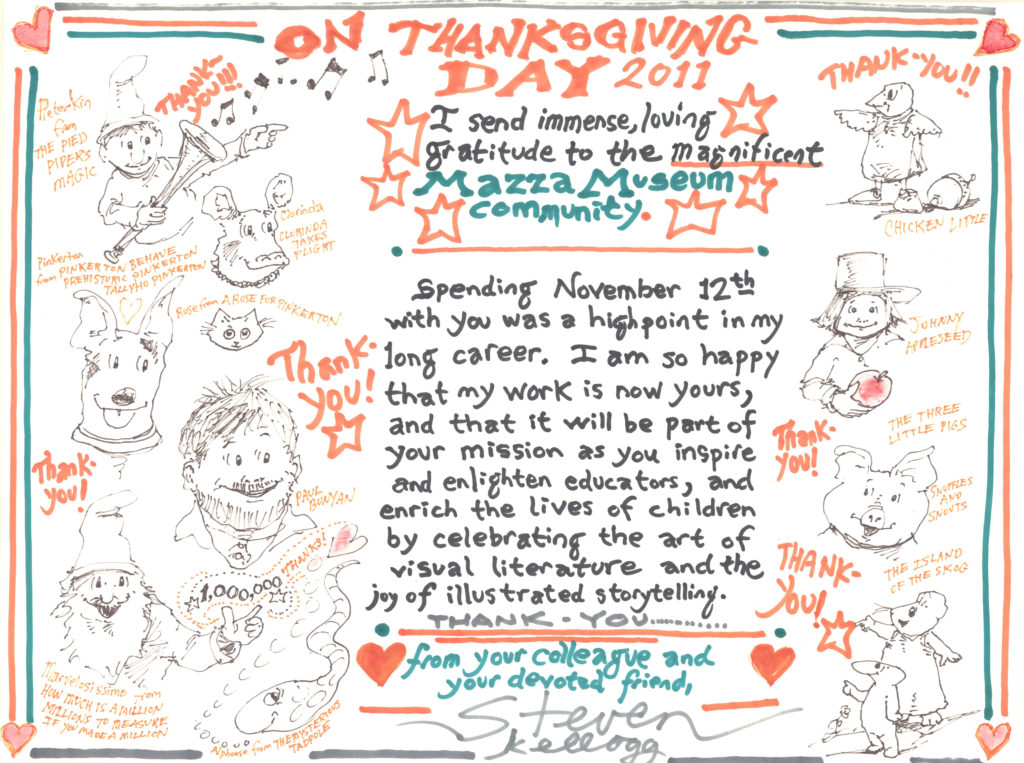

Born in Norwalk, Connecticut on Oct. 26, 1941, Steven Kellogg has written and illustrated more than one hundred picture books. In a career highlighted by countless accolades, Steven has the distinction of being the first illustrator to donate his entire life’s work to the Mazza Museum. On Nov. 12, 2011, during the Weekend Conference, Steven donated 2,247 works of art from 109 of his books. His gift included the preliminary drafts and Dummy books for each of his publications (three of which are now on display in the Wilson Gallery) and increased the size of the museum’s collection by forty two percent. In appreciation for Steven’s generosity and in celebration of his creative legacy, the University of Findlay presented the esteemed author/illustrator with an Honorary Doctorate.

An early childhood interest in making up stories and drawing pictures to go with them to entertain his sisters, has blended together with Steven Kellogg’s love of animals in a very successful combination. After graduation from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1962, Mr. Kellogg became fascinated with the picture book as an art form, and immediately turned his illustrative talent in that direction. It cannot be a secret that this gifted artist finds his work of designing picture books exciting and challenging, for the pages of his stories fairly overflow with his freshness of spirit, originality of story line, and the charm and humor of his characters. Children immediately take his endearing characters to heart, especially the animals, for their appeal is irresistible.

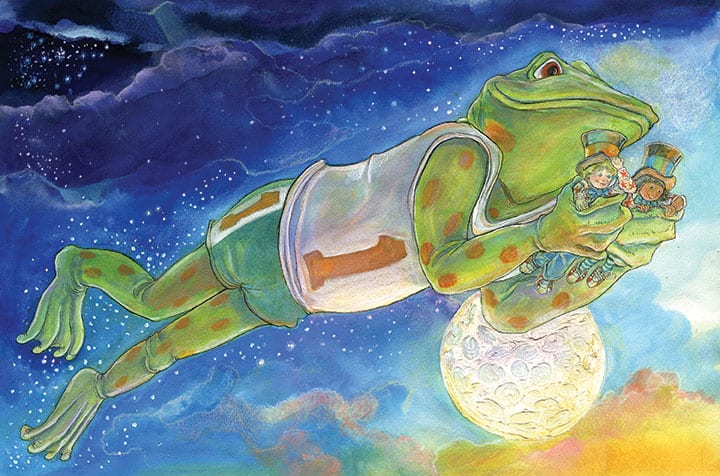

Steven Kellogg believes that there is no one “best” method or technique for picture book illustrations. He is committed to the belief that books should be available to fit the varying individual tastes of children, and that this individuality should be encouraged. He also fits his style and technique to the requirements of a particular story so that a book of great strength and “rightness” will result. He further explained, “I use colored inks, watercolors, acrylic paints, and various types of pencils, trying to pick whichever one will best express the feeling or mood I want for a particular illustration. I work somewhat intensely, and I like to surround myself with my materials so that the momentum does not have to be interrupted by a search through cupboards and drawers when I suddenly need a certain color, pencil, or brush.”

Kellogg has used a variety of techniques in his full color artwork; in his later books he usually employs a combination of colored inks, watercolor, and acrylics. Not all of Kellogg’s books have a design line; especially with his early books; publishers didn’t always use his work to the best advantage. Of Kellogg’s more than eighty picture books, the retellings of tall tales and folk tales achieve the best match of story and illustration.

When asked how he got his first book published, he said, “I’d always been interested in doing books, but I was interested in many kinds of artwork at the same time. I wrote a story called “The Orchard Rat” and sent it to a publisher. On the basis of the sketches I sent with it, they asked me to illustrate a number of books. After much rewriting, the original story was published as The Orchard Cat.”

One of the Steven Kellogg art pieces in the Mazza Museum is a beautifully executed etching, an intriguing piece that reveals many of the characters from his books…Secondhand Rose, and Pinkerton, everyone’s favorite Great Dane, among others.

Several of Steven Kellogg’s books are illustrated in the combination of black line drawings and halftones and color washes, reproduced in color through a special camera separation process. The work, from Tallyho, Pinkerton!, is an example of this special process. The artwork was prepared on two sides of a thin piece of handmade watercolor paper. It was executed on a piece of glass, with a lamp placed underneath so that the line could be seen when the artist was working on the color side. The reason for separating the black line and the color is so the line can be photographed and reproduced as a solid line (insuring greater sharpness and clarity) while the color is reproduced as halftone, a process in which tonalities are determined by dot densities. The halftone method of reproduction captures subtle modulations of color, but it is less successful in reproducing the crisp black lines that structure the details of Mr. Kellogg’s illustrations. It is interesting to compare the original artwork with the finished book illustration.